By Paul Barry

December 28, 2005 SMH

Illustration: Rocco Fazzari

AUSTRALIA will never be quite the same again. He shaped this country's television, transformed cricket around the world and rampaged through corporate and political Australia in a style that none will ever match.

Politicians and ministers quailed at his call. Rival businessmen wilted under his attack.

On the racetrack, bookies trembled at his approach, while casinos either closed their doors or rubbed their hands with glee.

Kerry Packer was Australia's richest man, perhaps the world's biggest gambler and a huge and dominating presence for 30 years. Whatever he did, he did it large and loud, without apology.

Employees at Channel Nine and rivals in TV spoke of him as the rudest and most frightening man they ever met - they didn't know his father, Sir Frank - yet he also commanded huge loyalty and affection. Though brutal, he could also be charming, polite and extraordinarily generous. Like his father before him, he was an enigma: a man of moods and contradictions, often isolated, lonely and unhappy.

Kerry Packer was one of the most powerful people in Australia, and here's why: he was a billionaire, which was a good start; he owned the nation's top TV network and a stable of magazines, which was even better; and he was extremely smart and negotiated well, which guaranteed he made the most of his advantages. But most of all, he was a terrifying man to say no to.

Face to face, he was quite formidable. Put simply, he inspired fear.

Unlike Rupert Murdoch, Packer very rarely used his magazines, newspapers or TV stations to attack governments. As a general rule, he did not tell his journalists whom to attack, whom to support or what to write.

Yet successive governments, including the current one, were so worried about what he or his media outlets might do that they rushed to give Packer what he wanted, almost before he asked.

The decision in 1986 by the Hawke government to permit TV companies to own networks across Australia more than doubled the value of Packer's Sydney and Melbourne Channel Nine stations, and allowed him to sell to Alan Bond for $1 billion.

The restrictions imposed on pay TV by the Keating government in 1992 were similarly slanted in favour of the big man. And the Howard Government was no better. Its 1999 decision to guarantee the commercial TV networks a monopoly until 2007 benefited the Packers enormously.

For two decades and more, politicians came running when Packer called. And if he wielded more power than is healthy, it was because governments let him do so. Even prime ministers went out of their way to be nice to him.

When Packer sold Channel Nine to Bond in 1987, the program makers organised a testimonial video for their departing boss. All the stars joined in to sing his praises. But the real star was Bob Hawke, who introduced the proceedings from his garden at Kirribilli House.

Straight to camera, one powerful man to another, he gave the big man a ringing personal endorsement: "G'day, Kerry, I don't think anyone has made a greater contribution to television news and current affairs than you."

He followed up with a heartfelt homily on Packer's treatment at the Costigan royal commission, in which Packer had been famously accused of involvement in organised crime, drug smuggling and even murder, under the code name "the Goanna".

"I don't think any figure in Australia has had to bear such a burden as Kerry Packer," said Hawke, "with the unjustified innuendos, slanders, the malicious gossip.

"And it was all untrue. Loyalty is a two-way thing, Kerry. You've certainly given it to your people. I hope you feel that all of them and all of your friends have stuck by you. You deserve it."

Far more recently, John Howard has publicly defended Packer's meagre tax-paying record, when he could just as easily have attacked it, showering praise on Packer's generosity to charity and his record as a good corporate citizen.

Bob Carr has also joined the queue of homage-payers, telling The Daily Telegraph while premier of NSW that it was vital for the economy that Packer recovered from a health scare.

In business Packer wielded huge power, bullying and threatening those who got in his way. Steve Cosser and John Gerahty, who ran Channel Ten in the early 1990s and tried to challenge Channel Nine's dominance of the TV market, were two who felt the full force of Packer's wrath.

Cosser remembers being told: "If you think there's no difference between being No.1 and No.2 in a f---ing two-station market, then you be f---ing No.2."

Gerahty was summoned to Packer's office to be treated to a tirade that had him still shaking months later. The big man's message was that Channel Ten should not compete against Packer's station and should not bid against Channel Nine for programs. But the style was even more shocking. According to Gerahty, Packer's manner was threatening and his language was coarse and abusive.

Packer's attitude to journalists was much the same, especially if they were writing about him or his business. He held most of them in contempt, along with politicians, and rarely talked to them. When he did do so, it was usually to complain that no one ever checked stories with him or asked for his opinion.

When I wrote The Rise and Rise of Kerry Packer in 1993, he threatened to "prosecute [me] with the utmost vigour" and warned me that he would also sue "any other person who has any involvement whatsoever in the production of the book and the provision of information to you".

He tried to ensure that employees and friends did not talk to me. But while some journalists who wrote about Packer ended up being sued personally, so that their houses were on the line, I escaped. I even ended up working for him.

Even though he insisted on his privacy, his media empire regularly dished the dirt on other people's private lives. But, to his credit, he was a key factor in making Channel Nine a leader in commercial news. 60 Minutes was Packer's baby, as was the more serious and upmarket Sunday.

Packer's talent in television and, to a lesser extent, in magazines, was to know what worked and to go for it. He hired the right people and inspired them to give him the best.

On a broader canvas, he did what rich men do. He showed great skill in turning a $100 million inheritance into an empire that is worth some $7 billion today. And he did so without succumbing to the excesses of the 1980s, or committing corporate crimes.

He also gave back. While he did not pump billions into a charitable foundation - as so many rich Americans have done - he did give millions of dollars to the Children's Hospital at Westmead and the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney. And he helped many friends, and friends of friends, when they were in trouble.

But paying tax was another matter altogether. His policy, like that of his father before him, was to pay as little as possible and to employ an army of lawyers and accountants to find loopholes in the law.

In the 1970s, tax investigators were constantly on his tail and on more than one occasion he was forced to settle out of court to avoid the risk of prosecution. In the 1980s and 1990s the Tax Office's audit teams were also on his case.

The problems with Costigan - who was interested in large deliveries of cash to Packer - stemmed largely from tax schemes he engaged in to avoid paying his dues. As he famously told the nation in 1991 during the televised Senate inquiry into the media, only a fool paid more tax than he had to and he didn't think politicians were spending his money so well that he wanted to contribute more.

Packer's business empire is owned through a holding company in the Bahamas and ultimate control rests with a string of family trusts. The clear purpose of such arrangements is to keep tax payments to an absolute minimum. So much for the concerned corporate citizen.

Meanwhile, he spent big on having fun, or trying to. Hundreds of millions of dollars went on playing polo (building lavish facilities on three continents) and he gambled hundreds of millions more in casinos, racetracks and foreign-exchange markets.

At the Sydney spring carnival in 1987 he was reportedly $28 million down to the bookmaker Bruce McHugh on the last day of racing, then backed three successive winners to end up $2 million ahead. Two days later, a shaken McHugh walked into the Australian Jockey Club offices and handed in his bookmaker's licence.

Packer's worry when he took over the family business from his father was that he might lose his inheritance and take the Packers from shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations. But his worries were groundless. And there is no need to fret about his son, James, despite the One.Tel fiasco in which the Packers' public company, PBL, lost $400 million.

James may not have his father's uncanny instinct but he has a good team of people around him and has already taken the important (and successful) strategic decision to concentrate on casino and internet gaming. With Kerry gone, Channel Nine may be sold, but it was probably on the block anyway.

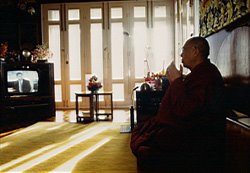

Sadly, no one was able to ask Kerry the question that was posed to Sir Frank Packer in his twilight years in a wonderfully grovelling interview on ABC TV in 1970. "Your father was a pioneer and you have become a legend," the great man was asked. "What is left for your sons to do?"

"Plenty" should have been the answer. And it might have been if Kerry had been asked it before his death.

There will be plenty more to come from James. I can't see him going off to grow vegetables. He may not be so much fun to watch. He may not spawn so many stories. His style is not so loud and brutal, thank heavens. But James is smart and tough and he has learnt at the feet of the master.