New Scientist vol 180 issue 2421

15 November 2003, page 34

Human chimeras were once thought to be so rare as to be just a curiosity.

But there's a little bit of someone else in all of us, says Claire

Ainsworth, and sometimes much more...

EXPLAIN this. You are a doctor and one of your patients, a 52-year- old woman, comes to see you, very upset. Tests have revealed something unbelievable about two of her three grown-up sons. Although

she conceived them naturally with her husband, who is definitely

their father, the tests say she isn't their biological mother.

Somehow she has given birth to somebody else's children.

This isn't a trick question - it's a genuine case that Margot Kruskall, a doctor at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, was faced with five years ago. The patient, who we will call Jane, needed a kidney transplant, and so her family underwent blood tests to see if any of them would make a suitable donor. When the results came back, Jane was hoping for good news.

Instead she received a hammer blow. The letter told her outright that

two of her three sons could not be hers. What was going on?

It took Kruskall and her team two years to crack the riddle. In the end they discovered that Jane is a chimera, a mixture of two individuals - non-identical twin sisters - who fused in the womb and grew into a single body. Some parts of her are derived from one twin, others from the other.

It seems bizarre that this can happen at all, but Jane's is not an

isolated case. Around 30 similar instances of chimerism have been

reported, and there are probably many more out there who will never

discover their unusual origins.

While cases like Jane's are the extreme, researchers now think that

there's a little bit of chimera in all of us, and what was once seen

as a biological oddity may serve a vital function. We may owe our

lives to being chimeras.

At first, Jane's case had Kruskall completely puzzled. The original

data came from the tests done to "tissue-type" her and her children.

Such tests are based on a set of genes called the HLA complex, which

encode many different immune proteins, including cell surface proteins that immune cells use to distinguish the body's own tissues

from foreign material. There are hundreds of different versions, or

alleles, of each HLA gene, and because of this, each person's

combination of alleles is almost unique. But because the genes are

clustered close together on chromosome 6, they tend to be inherited

together in a block known as a haplotype. Everyone inherits two HLA

haplotypes, one from each parent.

Transplant doctors know that the closer the match between two people's HLA haplotypes, the lower the risk of a transplant between them being rejected. If you need a transplant, the obvious place to look for people with a similar haplotype is your close family. Your siblings, for example, have a 1-in-4 chance of matching yours exactly, while your children will have at least 50 per cent of your HLA genes.

Confronted with Jane's bizarre test results, Kruskall's team's first line of enquiry was to take another look at Jane's HLA genes and those of her immediate family. They identified Jane's haplotypes and dubbed them 1 and 3. They tested Jane's husband too - he had types 5 and 6. And when they looked at her sons they confirmed that the original tissue-typing was correct. While all three shared a haplotype with their father, only one shared one of Jane's. The other two sons had a haplotype of unknown origin, labelled type 2.

The obvious interpretation was that Jane was not the biological

mother of two of her sons, yet they were all conceived naturally,

so how could this be? One possibility was that both boys were

accidentally swapped at birth, but the chance of this happening twice to the same family is very small. Add in the fact that both sons share a haplotype with their father and it becomes a near impossibility.

Stumped, Kruskall sent her data out to colleagues, asking them if

they could make sense of it. Soon researchers around the world were

scratching their heads in bewilderment. "I did get the most amazing

set of explanations," Kruskall recalls. "No one could quite figure it

out." One suggested that Jane had secretly undergone fertility

treatment using donated eggs. Another speculated that Jane and her

husband had got her sister to conceive children with his sperm, and

then pretended they were hers.

The breakthrough came when Kruskall's team checked the HLA haplotypes of other members of Jane's family who had been omitted from the original tests. They discovered that her brother carried the mystery haplotype 2 - suggesting that the two sons were related to Jane in some way after all. "That really provided the spur that kept us going," Kruskall says.

So where did the sons' odd haplotype come from? Since Jane's blood cells provided no match, the team decided to test DNA from some of her other tissues, including her thyroid gland, mouth and hair. What they discovered was astonishing. Some of her tissues carried haplotypes 1 and 3, while others contained 2 and 4 (The New England Journal of Medicine, vol 346, p 1546). Jane's body was made up of two genetically distinct types of cells.

There was only one conclusion: Jane was a mixture of two different people.

Kruskall thinks the most likely explanation for this is that Jane's mother conceived non-identical twin girls, who fused at an early stage of the pregnancy to form a single embryo. In medical parlance, Jane is a tetragametic chimera, a person whose body is made up from two genetically distinct lines of cells derived from a total of four gametes - eggs and sperm.

This instantly explains why the tissue-typing yielded such paradoxical results. For some reason, cells from only one twin have come to dominate in Jane's blood - the tissue used in tissue-typing. In Jane's other tissues, however, including her ovaries, cells of both types live amicably alongside each other, hence the apparently impossible genetics of her three sons. One came from an egg derived from the twin whose cells dominate Jane's blood, while his two brothers came from eggs derived from the other twin's cells.

Nobody knows how common tetragametic chimerism is. It often has no outward signs and those who uncover their chimeric nature do so only by accident.

Nature reported a similar case to Jane's in 1979, when genetic tests

suggested that a woman could not be the mother of any of her four

children. There had been no hint that the woman was chimeric.

Some chimeras do have unusual physical features. For example, one

girl was discovered to be a chimera because her eyes were different colours, one brown, the other hazel. Others have come to light when doctors investigated problems with their reproductive systems, and

found that they had structures from both male and female reproductive

organs as a result of having cells of both sexes in their bodies. But most probably go through life utterly unaware of their unusual constitution.

"They are probably dramatically under-diagnosed," Kruskall says, "and also dramatically rare."

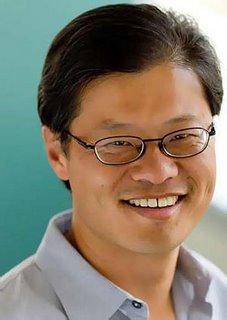

Yet this kind of chimerism may still be common enough to cast doubt on the way we carry out genetic tests of parenthood. Kruskall is currently helping out with a court case where a woman is suing her partner, claiming that he is the father of her child. In a bizarre twist that would nonplus even Jerry Springer, tissue-typing tests proved he was the father, but ruled her out as the mother. The situation could be explained by chimerism in the mother, Kruskall speculates.

But what about a case where the father was a chimera? "You could imagine that you could rule out a person who is in fact the father," she says. This is especially plausible if one cell line always comes to dominate in the blood, as happened with Jane. Animal studies of chimerism suggest that this is indeed common.

What's more, the incidence of tetragametic chimerism is set to rise,

Kruskall says, because of modern fertility techniques that increase the rate of twinning. Drugs used to make a woman ovulate can cause her to release more than one egg at a time, for example, while many IVF clinics still transfer more than one embryo into the womb. And the fact that embryos are in close contact in the lab dish or when transferred to the womb may encourage them to fuse, according to a report by a team at the University of Edinburgh, UK. In 1998, they reported a case of a chimeric IVF baby who resulted from the accidental fusion of a male embryo and a female embryo (The New England Journal of Medicine, vol 338, p 166). The child was outwardly male, but the left hand side of his internal reproductive system had developed as an ovary and fallopian tube.

Meanwhile, Jane's mystery is solved - and it even has a happy ending. Because her body contains double the normal number of HLA haplotypes, it means that she has a much greater chance of finding a suitable donor kidney.

But the story doesn't end there. There is growing evidence that chimerism in one form or another may not be so unusual at all. In fact, some researchers now think that most of us, if not all, are chimeras of one kind or another. Far from being pure-bred individuals composed of a single genetic cell line, our bodies are cellular mongrels, teeming with cells from our mothers, maybe even from grandparents and siblings. This may seem a little shocking at first. The thought of playing host to cells from other people may offend your sense of individuality. But you may have those outsiders to thank for keeping you healthy.

During pregnancy, the blood of the mother and fetus are kept separate, but some cells manage to slip through, meaning that you will have picked up some cells from your mother, and she some from you. In fact, some 80 to 90 per cent of women carry their children's cells or DNA in their blood during pregnancy and up to 50 per= centcarry them for decades after giving birth, a condition called microchimerism (New Scientist, 24 April 1999, p4). If your mother then had more children, some of your cells could in principle slip back through into your younger sibling's body. And twins can end up swapping cells in the womb, especially if they share a placenta. So a single person can be a veritable menagerie of different cell types from different generations. "Women harbour cells from both their mother and their children," says J. Lee Nelson, an immunologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

The fact that fetal cells persist in their mother's bloodstream for decades has been known since the mid 1990s. But only recently has anyone investigated how common it is for cells to move the other way – from mothers into their children. To investigate this, Nelson and her colleague Natalie Lambert have been searching for maternal cells in the blood of adult women.

In a forthcoming paper in the journal Arthritis & Rheumatism, they describe how they took blood samples from 32 healthy women and found that 22 per cent of them were carrying white blood cells from their mothers. These maternal cells were relatively rare - at most there were 50 per million blood cells - but Nelson suspects that more extensive tests of blood and other tissues such as bone marrow would reveal microchimerism in a far greater percentage of women. And the same goes for men too. "Our guess would be that it is probably universal," she says.

This discovery raises some puzzling questions. How come the invading cells don't simply get wiped out by the immune system? Do the cells divide inside their new host? And why do mother and child exchange cells at all - is it just an accident, or does it have a purpose?

In the case of fetal cells crossing to the mother, Nelson says we don't know whether it serves any specific purpose, but one important factor could be that these cells encourage the mother's immune system to tolerate her fetus. After all, pregnancy is rather like hosting a transplanted organ for nine months, and transplant researchers have known for some time that microchimerism caused by white blood cells from the transplant mixing with those of the recipient can encourage the host to accept the transplant under certain circumstances. And researchers think the breakdown of this long-term tolerance to fetal cells may be the cause of some autoimmune diseases in women (New Scientist, 24 February 2001, p 8).

"But what benefit [fetal cells] might offer long term, no one knows,"

Nelson says. As for cells passing from mother to fetus, there are hints that this may play a vital role in keeping the unborn child healthy. Your mother's cells don't just hang around passively in your body, Nelson believes. They might play an active role in repairing your tissues, especially while you are still in the womb. And she has evidence that unknown types of maternal cells cross the placenta and then "transdifferentiate" or transform themselves into different kinds of cells that then become part of the baby's body.

Anne Stevens, a researcher in Nelson's team made the discovery while

studying the bodies of babies who had died from an autoimmune disease

called neonatal lupus syndrome, which attacks heart muscle. In the course of testing the heart cells, she found that the babies' hearts contained muscle cells that could only have come from their mothers. Nelson says she can't yet be sure exactly how they got there, but thinks it likely that blood stem cells from the mother made their way to the heart of the developing fetus and transdifferentiated into heart cells. "It really is amazing," she says. "This is really the next conceptual leap in the entire field, I think."

The question is, what are these maternal cells doing? Are they the cause of the autoimmune disease in the children or are they trying to intervene? One possibility is that the presence of the maternal cells triggers the baby's immune system to attack the heart.

Mother and child usually tolerate each other, but if this were to break down, the fetus's immune system would identify the mother's cells as foreign and attack them, with the fetus's own heart cells getting caught in the crossfire.

But Nelson thinks there is another, more positive explanation. "The second possibility is that the maternal cells are there trying to repair the damaged tissue," she says. Her results don't yet tell her which explanation is correct, but she says: "I always go back to remembering that there could well be beneficial functions because [microchimerism] is so common in healthy people."

While microchimerism may force immunologists to rewrite their textbooks, it may also prod us into seeing ourselves in a new light. Rather than being isolated individuals, perhaps we should see ourselves more as a collective - an individual made of many other different individuals. On one level, you are you, a person with your own thoughts and feelings. But zoom in one level and you are a supercolony of individual cells, some cooperating, others competing. Zoom in to the level of your genome, and you find individual chromosomes and genes, all jostling to get through to the next round of natural selection. It's all a question of perspective.